Dance in a Time of Unrest

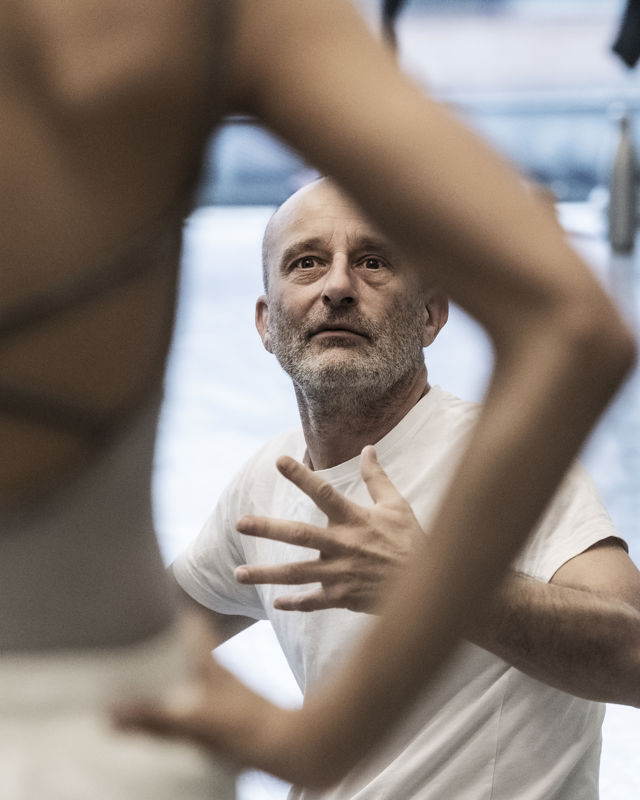

Jo Strømgren / Photo: Erik Berg

Jo Strømgren / Photo: Erik Berg

– It would have been easier to be interviewed about another performance, because this one is more abstract. And when it comes to the abstract, perhaps it's best to say as little as possible.

It's been 30 years since Jo Strømgren made his debut as a choreographer. Over 200 works are listed on his CV, including nine for the Norwegian National Ballet, where he has been choreographer-in-residence since 2013.

Stigma will be his most abstract work to date.

– There are still ways to talk about abstract ballet, though. Suggesting possible meanings is a disservice, because it could steer interpretations and associations. And I don't want that. But it's interesting to talk about what one fundamentally wants to express.

He says he has found himself in a small dilemma this time. Many associate Jo Strømgren with performing arts that are very concrete: Clear language, albeit in a made-up dialect. Distinct characters, a plot from A to Z. Politics. Humour.

– Not necessarily easy to access, but it is accessible, at least, he adds.

With Stigma, it will be different.

– We live in a time of great change, and I sense an ever-growing unrest. People are walking around worried. There is confusion, uncertainty about what is happening or what will happen. This unrest is reflected in politics, between people, and when you sit alone, mulling over things.

How can such unrest be expressed—through dance?

– Right now, I don't think it’s suitable for clear opinions, shouts, or truths, says Jo. – The topic is too complex for that. Therefore, I chose to make it a bit more abstract, more intuitive—to find feelings that perhaps many share today, including myself.

The Ballet Performance "Hi"

If the work is abstract, it still has a concrete title.

– The title is concrete, yes, says Jo. – But at the same time, very open.

The word stigma is Greek, meaning mark. It is often used in the plural form, stigmata, referring to the wounds of Jesus from the nails on the cross.

– But in everyday speech, we often talk about being stigmatized—being marked—about a kind of inheritance you carry as a person, or as a family or group, that has nothing to do with you or the group you belong to, but something that has happened before. Something you carry with you. A kind of original sin.

Titles for abstract ballet can be anything, according to Jo.

– It could have been Hi the ballet. But since the point is to reflect on something as little fun as unrest, unfortunately, the title wasn’t Hi this time.

And the word stigma undoubtedly triggers associations. There’s something about the mass of dancers, the processions on stage, the cross formations, and the costumes that can easily be linked to the title.

– I won’t claim to be 100% abstract. It’s just not in my nature, admits Jo. – But this is the most abstract thing I’ve done with the Norwegian National Ballet. But abstraction in itself only becomes exciting when you manage to spark thought processes in the audience. The question is always: How much do you need to set that process in motion?

Is there a small bloodstain at the front of the stage? Or is it the costumes or music that suggests something? Are there theatrical progressions, or can it be completely random images?

– It’s hard to calculate. But as little as possible is often the best—then the thought processes can stretch even further.

Santa’s Workshop

Having worked as a choreographer for three decades, in 70 different countries, Jo Strømgren has encountered a lot of people along the way. Not to mention various groups. Jo has one foot in the independent performing arts field, one in institutions, and has worked across genres with theatre, dance, film, opera, and puppetry.

– It’s very interesting to see the types of people you’ve worked with in different projects and countries, Jo explains. – Different ages, social classes, political beliefs, religions, physical variations, ideologies, and perceptions of what art is or should be.

One thing he is sure of: If you’re going to work in theatre and dance, you have to be interested in people.

– If you don’t like the differences among us, you need to find another job.

This time, he’s back with the Norwegian National Ballet: A company that is like a miniature world in itself, with dancers from over 20 nationalities—and with a strong ballet culture that crosses borders.

– It’s a great privilege to be a part of the National Ballet as a resident choreographer and guest, Jo says. – Over the thirty years I’ve been working, I’ve seen an incredible development in what the Norwegian National Ballet is and has been, and what kinds of people are allowed to flourish within those frames.

He’s working with the company for the eleventh time now—and is surprised.

– Normally, I lead the way, set the movements, and make a lot of decisions. But I thought: Now, I’ll take a step back, because the ensemble I have in front of me is so curious, so creative, and there are so many types of personalities, he says. – It’s a bit like Santa’s workshop. Everyone is working in all corners. I don’t need to shout. The National Ballet is on its way.

The dancers have been more creative than before.

– They’ve definitely contributed with movement material this time, says Jo. – And being able to use their own body language on stage is a privilege all dancers deserve now and then. I preferred it myself as a dancer, and I hope more choreographers let dancers express themselves that way. But it’s also important that I, as a choreographer, take responsibility for most of the material and add a clear signature. Dancers already have a hard everyday life, and if they’re pushed too much creatively, their heads could explode. Voluntarism is important. But of course, it’s a joy to be served food on a silver platter, and this time I’ve eaten well.

Night and Day

As if choreographing weren’t enough: Jo is also the set designer for the performance.

– I’ve become quite used to working on several tasks at once, he explains. – The more responsibilities I can take on myself, the better it is for the idea and the process. But of course, there are limits, and hubris. There are many things others are much better at.

For the work on Stigma, he’s collaborating with lighting designer Oscar Udbye and costume designer Bregje van Balen.

– Without them, I wouldn’t have been able to pull this off. No chance.

As for the music, he has a long-standing collaborator. As he says: Some friends never disappear.

– I have one: Bergmund. He’s my best friend from childhood and adolescence. We’ve worked together a lot. So, we’re a bit like the Katzenjammer Kids as often as we can.

Bergmund Waal Skaslien is a violist and composer and has also worked with the Norwegian Opera Orchestra several times. The music in the second act of Stigma is his, from previous works.

– We have two acts in the performance, and the expectation in the world of theatre is that act one and act two should be somewhat different, otherwise, the break between them doesn’t make much sense, Jo says.

In the first act, the music is modernist; by Romanian-Austrian György Ligeti and German-Russian Alfred Schnittke.

– This is hardcore 60s and 70s pling-plong music that interests me when you combine it with, for example, dance, Jo explains. – But it’s not something I sit and listen to alone in the evening. Or, well, sometimes. Oops, I guess I let the cat out of the bag.

Skaslien’s music in the second act he describes as more nostalgic, warmer—perhaps with a bit more hope.

– So there’s a kind of yin–yang, night-and-day composition to the evening as well. I think it’s nice to start off a bit cold and hopeless, but … when you return after the break, it’s perhaps almost a responsibility to bring some hope, warmth, and a slightly rounder perspective on things.

From the Bible to Darwin

Jo is keen on the use of references.

– I feel it’s incredibly important, at least in an art form like dance theatre, to be aware of the common references the audience possesses.

He tells a story about a time he staged a performance in New York and used text from the French philosopher Jacques Derrida—references that no one understood.

– There’s no point in loading a performance with references people don’t get. It’s wasted. But this is interesting because it makes you think: "What are our common references?"

He says he’s becoming more and more aware of how many Christian values our society is built on.

– Christianity has more to do with us than many people think. So when I use simple images in a performance that remind us of something from biblical stories, we recognize it. I have to be careful here, though, because even though I’m an atheist, I’ve read the Bible many times and consider myself more than well-versed in theological references. There are Derrida traps there too.

He adds: – A Norway today is much more multicultural and diverse, so common references are becoming blurrier. Now it’s perhaps on the internet and in popular culture that our common references are being created.

Without giving too much away: In Stigma, we also encounter some exotic creatures from the animal kingdom.

– When it comes to symbolism, I feel that it’s not enough only referring to religion to express our place in world history, says Jo. – We must also deal with what we struggle with, the friction, which is Darwinism. Those are the two axes we still wobble between. That discussion never ends.

Where Stigma features several biblical references, Jo also includes elements that evoke this other axis.

– We’ve evolved. We’re not high-born spiritual beings. We’re actually primates. So, there are two pretty radical symbolic references that clash a bit in the performance, and I hope we can create some tension there.

Back to the Base

Jo has survived for a long time in the performing arts field.

– That he hasn’t lost his drive must mean he’s chosen the right profession. Or, for me, it’s better to say that it’s the right channel for my anger, irritation, or whatever I want to express and share.

While often working across genres, with Stigma, he’s returned to the core of his work: dance.

– "Choreographer, stick to your craft," someone wrote in a review when I staged theatre for the first time. Two stars. But the Norwegian newspaper VG saw it differently and gave it six stars. Many probably want to keep people on the shelf they’ve put them on. But that’s not what art is about. In a free country and society like ours, there’s a responsibility to explore, to find new connections, Jo says.

But it’s always a relief to return to the elemental, he thinks.

– The base, right? In theatre: words. In film: images. In dance: movement. That’s our anchor. As part of the dance environment in Norway and Europe, I sometimes think we shouldn’t forget that it’s the body and movement—and what it can express—that is the foundation of what we’re doing. We need to return to that purity now and then.

Even with 30 years of experience, creating a main stage performance is nerve-wracking.

– It’s always just as difficult. In a place like this, where everyone is so incredibly competent, and they bend over backward for the idea you have, doubt always creeps in. Am I a fraud who really has nothing to say? But the best thing is not to think too much about it and just go bananas in the Lego box. And that’s what the Opera is—it’s a huge one.

But sometimes, at night, it comes. Not necessarily performance anxiety, but thoughts about—

– Responsibility ... yes, responsibility. Privileges shouldn’t come for free.

Veronika Selivanova og Sonia Vinograd / Photo: Erik Berg

Veronika Selivanova og Sonia Vinograd / Photo: Erik Berg