Pite's passages

Passage / Photo: Erik Berg

Passage / Photo: Erik Berg

"It’s too famous. It’s too well-known. I can’t.”

The year is 2016, and Crystal Pite has been commissioned to create a new work for The Royal Ballet. It is the first time in 18 years that a woman is choreographing for their main stage. For the Canadian choreographer herself, there is something quite different grinding in her mind.

– At that time, the world was in the thick of the Syrian refugee crisis, she recalls. – I was finding it hard to concentrate on creating a new piece, I just got really caught up in the news and felt a sense of helplessness and hopelessness. I didn’t feel like choreographing a piece at all.

A choreographic writer’s block, you might call it. Even she, one of the world's most sought after in her field, feels vulnerable in the face of a new work. Clean slate.

Symphony of Sorrowful Songs

Górecki's third symphony was to beat that block.

– Somehow it was Gorecki’s music that made me feel like I could approach the subject of refugees, Pite says. – I think his third symphony, for many people, is a kind of place of communion. It is a musical embodiment of suffering and humanity. I think that many people have connected to it through various crises. And I felt like these three things kind of came together; what was happening at current events, the music, and the opportunity to create this new work.

But at first, she dismissed the idea. Who doesn't already know Góreckis Symphony of Sorrowful Songs?

– I think it’s the best-selling contemporary classical symphony CD that has ever been sold. “Maybe it’s just too famous and I should look for something else.”

So she did. She went through piles of orchestral pieces.

And came right back to Górecki.

– Then I ended up settling on that.

The result was Flight Pattern. A powerful one-act with 36 dancers set to the first movement of Górecki's third. The title refers not only to the theme, the fleeing pattern, but also to the choreography: a crowd of people moving in specific, repeated patterns, with individual dancers breaking away from the group to later find their way back.

– The title also reflects the fact that these humanitarian crises happen again and again. The feeling that they are repeated across cultures and generations, and the pattern of human migration across territory and time, she says.

How do you bring up such a serious topic – through dance?

– It’s a subject that I can’t possibly understand. I can’t possibly imagine what it’s like to be a refugee.

It is not the first time Pite brings something heavy-hearted to the dance mat. She has always kept her finger on the pulse of the real world. Through her 30 years as a choreographer, she is considered a master in transforming trauma and deep human pain into stage art. Take Betroffenheit, for example, created together with Jonathon Young for Electric Theater Company and Pite's own company Kidd Pivot: The award-winning work is based on a tragedy from Young's own life. He woke up to find that the cabin next door was on fire – and the lives of his 14-year-old daughter and two nieces were lost. Pite and Young created a scenic language together that could convey the indescribable experience of shock and grief.

– Often when I work with content that is beyond me, beyond my experience, beyond my understanding, I try to make it personal, Pite tells. – I try to think about my own relationship to the subject. I zoom in and zoom out in the work choreographically and in terms of the content; out on the large picture, and then in on one personal human story within that.

Some dance first and choreograph later. Crystal Pite has always done both. Already as a child, in the Canadian city of Victoria, she puts together her first dance sequences. Later, as a dance student, her fascination for choreography grows. At the age of 17, she is hired as a dancer at Ballet British Columbia – and two years later, in 1990, she debuts as choreographer with the piece Between the Bliss and Me for the same company.

Yet another 20 years will pass before she takes the step over to work full-time as a choreographer. After her time at Ballet British Columbia, she spends five years dancing at Ballett Frankfurt under the direction of William Forsythe.

– When I was a company dancer, I always found time to go off and choreograph on other companies, she tells. In 2001, she established her own company, Vancouver-based Kidd Pivot, where she herself danced for ten years. When her son Niko was born, she let go of her life as a dancer and switched to choreographing and directing.

– But I’ve always done both, and my experience of being a dance artist has always woven those two ideas together.

Half the year is devoted to work with Kidd Pivot at home in Vancouver. The rest of her time is spent on commissioned work for other companies.

– I work at a very different scale and at a different pace when I make a work outside my own company, she admits, – it’s usually large scale, faster paced. Which I really enjoy; I enjoy the extremes of that, making a piece for The Royal Ballet, for example, in contrast to making something for Kidd Pivot.

Extremes run like a red thread through her works. Contradictions. Contrasts. Conflict. Both physically and thematically.

– I like to think of a conflict within the body itself, a conflict or a contrast within the very subject of the work. So those two things I think complement each other well. And when we have conflict in the body, you know, two contrasting ideas, it can pull a dancer into a very interesting tension. Pressure, longing, and I think there’s an energy that comes with that that’s very compelling. I also like the opposite, which is a sense of playfulness and release, ease. So, all these kinds of tensions between things are interesting to me.

Nederlands Dans Theater, the Paris Opera Ballet, the National Ballet of Canada ... The companies she has worked with are numerous. Nevertheless: A Pite all-nighter is rare.

– I don’t actually make a lot of new work, I make a new piece maybe every 18 months on average. And the pieces don’t come easily to me, so I don’t make a lot of them. And once I do, I really labor over. I tend to be pretty fussy and probably overthink, she laughs. – That is just how I do it.

The dancers talk of a gentle, warm and cordial person – who is at the same time completely precise when the choreographic building blocks are put together. She painstakingly works with the details, right down to the microscopic level, in search of the precise physical image – the image that makes her work so poetic, and which is also the key to her way of communicating ideas, feelings and stories. Dance is her communication tool: a language beyond words.

Flight Pattern is gaining praise after its world premiere in 2017. Both the press and the public are shocked and excited at the same time, and Pite receives the prestigious Olivier Award for her work. When The Royal Ballet asks her to develop the work further from one to three movements in 2022, the refugee crisis has also taken on a new relevance in Europe.

– There’s that sense of repetition. Choreographically, repetition is a theme in the work, Pite Says. – You get a sense of these repeating storylines across generations. And we are part of that continuum.

But the new three-act Light of Passage, in which the orchestra plays Górecki's Third Symphony from start to finish, is not exclusively about people on the run. It is about transitions – passages in our human lives.

– Passages with thresholds and borders, and the sense of journey through something, whether it’s through a border or a checkpoint, from childhood to adulthood, from life to death.

The second movement, Covenant, deals with the passage from child to adult, but also the idea of creating safe passages. Safe journeys.

– Covenant is inspired by the United Nations’ Convention on the Rights of the Child, which consists of 42 articles. Some of them are very simple – like, heartbreakingly simple. You have a right to have a name. A child has the right to life and to be able to play and to be listened to. And of course, there’s an inherent sadness in that these need to be written down at all.

She wanted to try to embody them – to take the promises of the convention to the stage. See what they might look like as dance. In Covenant, the adult dancers become springboards and support for the young dancers on stage. In one moment the children are lifted above the stage as if flying into life itself - and in the next the children pull the adults behind them, like heavy chains

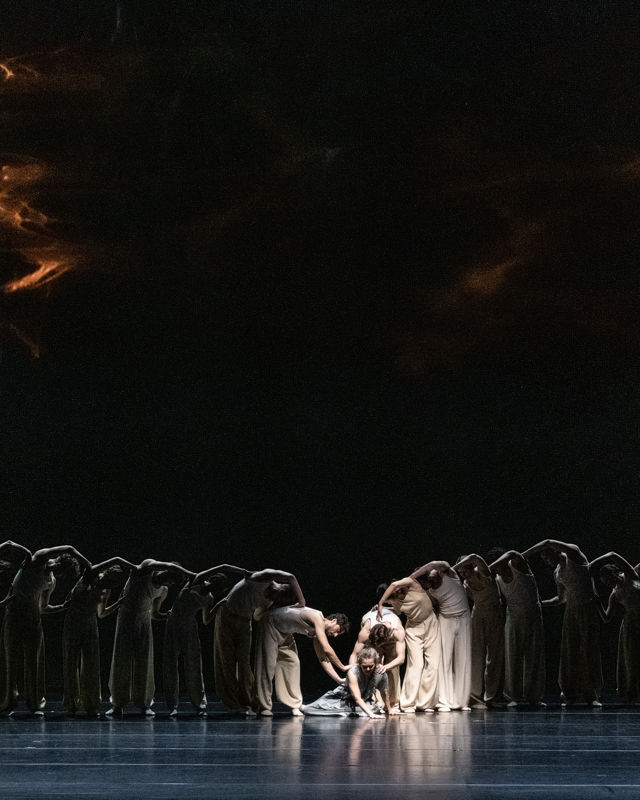

Finally comes the third movement, Passage, which, through two elder dance artists, depicts the ultimate border crossing: from life to death.

– So, the theme of passage runs through all three movements, in different ways, Pite sums up. Because she sees them as three different works. – In Flight Pattern, we are talking about the flight of refugees, as when people are moving from one life to another, Covenant is about the safe passage for children and the passage from childhood to adulthood. And then the third movement is an expression of the threshold between what we know and what we don’t know. And the immeasurable distance between the departed and the bereaved.

The subject matter is intense. But there is a hope and a belief that pervades all three movements.

– Though the themes of this creation may be difficult, I think there is a profound optimism in putting something like this out into the world and connecting to each other through it. There is something so inherently beautiful and joyful in people gathering around something to reckon with it. I want to create conditions in the theatre where we can gather around what we cannot know and grapple with it, together.

This optimism is also present in the title: Light of Passage. The ballet is not all heavy of doom and despair.

– Light of Passage starts in one place and ends up in another. For me, there is this interesting tension there, too, between the beauty and the brutality of humanity.

Again: A contrast. An opposite.

– The work deals with difficult content, but it also shows a kind of joy, a heightened sense of life. The source and the force of our vitality and our willingness, despite our inevitable separation from what we know and from those we love, to love and create and share anyway. I wanted to put that onstage too. I want to connect with others in that feeling of wonder and delight in our existence. Dance itself is a true expression of that.

Passage